No Filter?

To recap: Yesterday I shared a Reels from a young man who posts videos celebrating cinematic history and Hollywood. He declaimed his views on AI filters used on old Hollywood images – “modified to modern taste” – because these new filtered images overtake search results.

“It’s becoming more and more difficult to do research and see the past,” he said, “because we are replacing the past with this AI filtered junk.” He further warned “we are down a really dangerous path where it’s going to become impossible to find anything that is original without looking in books, and it’s going to be harder and harder to find those books.”

His comments called to mind the history of the publication of Dickinson’s poetry. Back in the 1890s, editors Mabel Loomis Todd and Thomas Wentworth Higginson “filtered” and modified her poems from the start to satisfy public taste, and it took years to sift through and publish them as she wrote them.

In her book Ancestors’ Brocades, The Literary Debut of Emily Dickinson, Millicent Todd Bingham shared what her mother had told her surrounding the editing recommendations and rulings she and Higginson had to make:

“When Emily Dickinson was unknown, her acceptance by the literary world problematical, such decisions were weighty. The poems chosen to introduce her must not be too queer. The editors never ceased to feel handicapped by this limitation.”

Due to the “problematical” nature of Dickinson’s work – including form, punctuation, capitalization, syntax, grammar, and more – established publishers in 1890 weren’t keen on printing her work.

Bingham’s father, David Peck Todd, told her that Colonel Higginson first recommended the poems to Houghton Mifflin Company for publication, as he was one of their readers at the time. They declined. The poems, they said, “were much too queer – the rhymes were all wrong.”

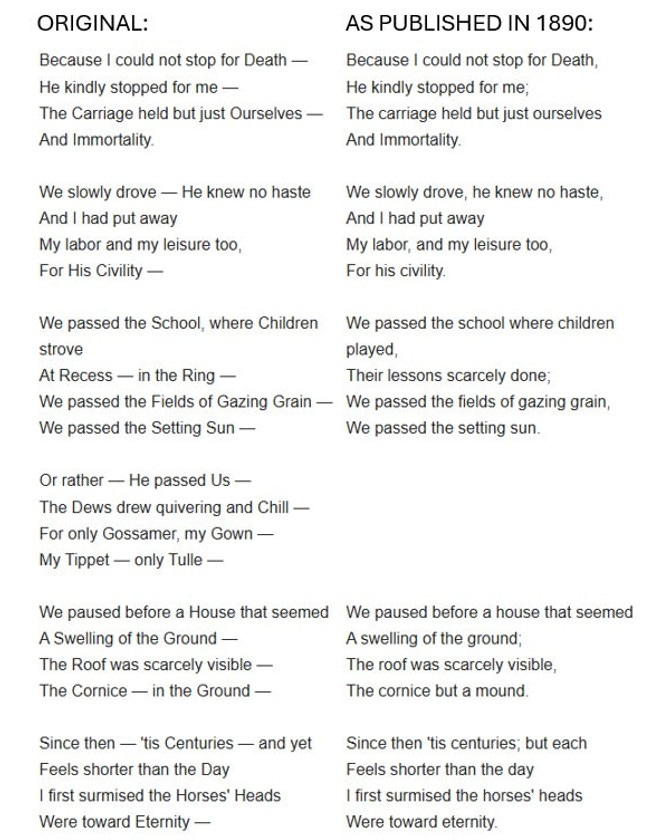

Whenever I come across a tome of Dickinson’s poetry, the first poem I check – to determine if the book contains original versions (i.e., as written by Dickinson) or the filtered versions – is “Because I could not stop for Death.”

If the third stanza reads, “We passed the school where children played / Their lessons scarcely done / We passed the fields of gazing grain / We passed the setting sun,” then I know the book contains edited versions of Dickinson’s poetry.

How do I know? Because Dickinson began the stanza with “We passed the School, where Children strove / At Recess – in the Ring.” Yes, in the original version of the poem, Dickinson rhymed “ring” with “sun” – and that was deemed “too queer” to publish in 1890. By the way, Todd and Higginson also completely deleted the fourth stanza from the poem. I have no idea why.

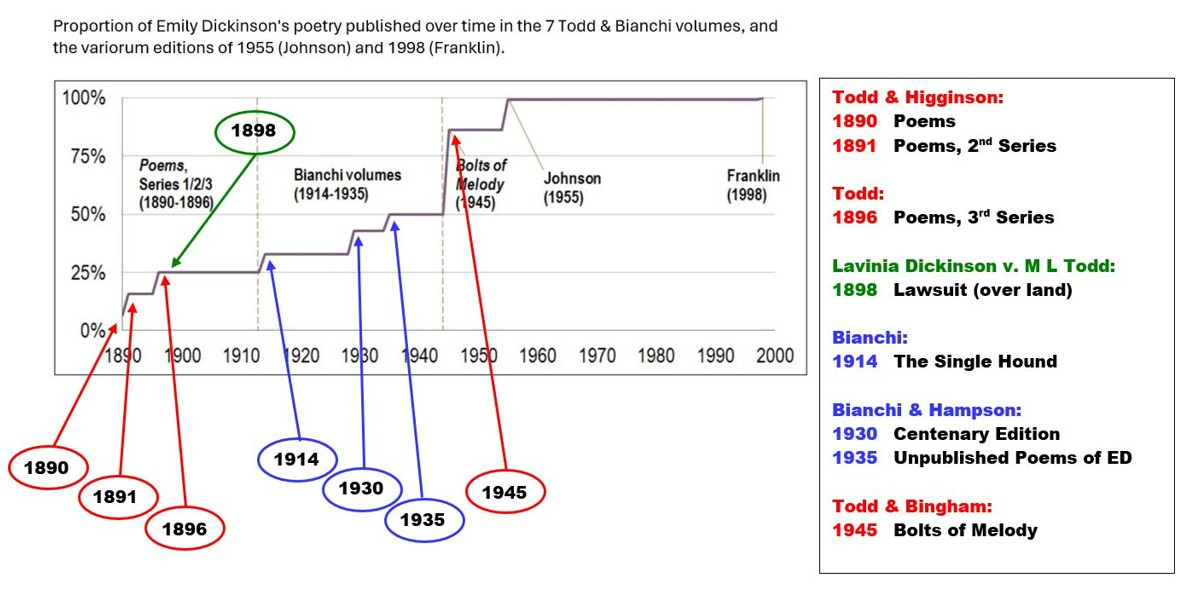

This editing – sanitizing? – of Dickinson’s poems went on for years. A first series of poems was published in 1890, a second series in 1891, and a third in 1896. The chart below shows dates of other editions, and it wasn’t until 1955 that a “complete” collection of her poems was edited and published by Thomas Johnson – and by this point, Johnson and other editors strived to present the poems as written.

Of his compilation, Johnson said, “The order of the poems is that of the Harvard (variorum) edition. There, where all copies of poems are reproduced, fair copies to recipients are chosen for principal representation.”

R. W. Franklin updated the “complete” edition in 1998, and he reported, “About three fourths of the poems exist in a signal source. For the rest, with from two to seven sources, the policy has been to choose the latest version of the entire poem, thereby giving to the poet, rather than the editor, the ownership of change.”

A recent update, published in 2016 by editor Cristanne Miller, is called “Emily Dickinson’s Poems as She Preserved Them.”

The poems as originally written. No filter.

Well…

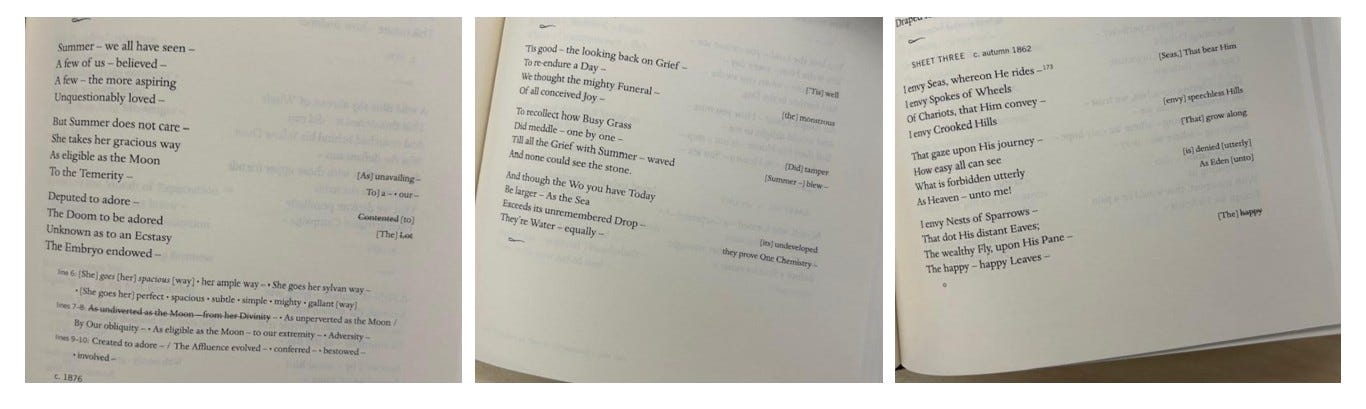

Things do get a bit foggy with some of the poems because Dickinson recorded numerous alternative word choices and phrases. The Miller edition includes the alternate possibilities on the right side of the page.